Biological Information¶

Biological systems and computer systems are analogous in ways that may not be immediately apparent. In this chapter we’ll briefly explore a relationship between the two: information processing is fundamental to both.

Central Dogma of Molecular Biology¶

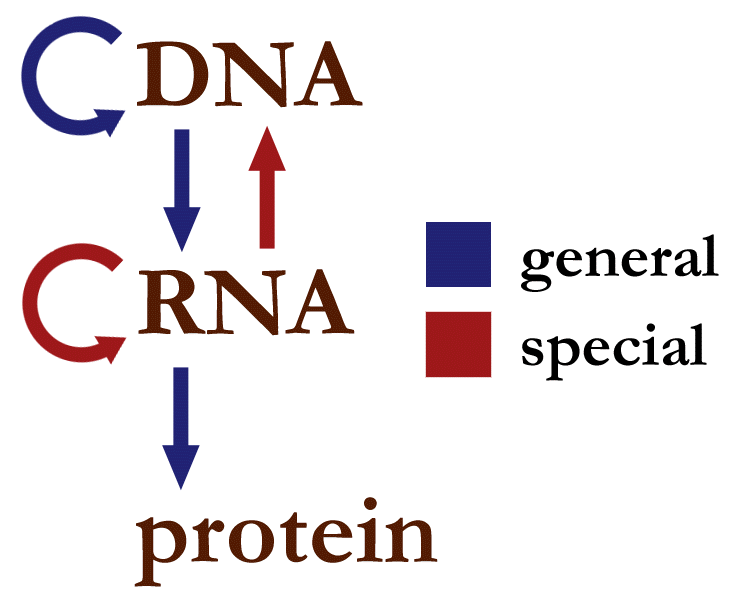

The Central Dogma of Molecular Biology (Fig. 1) describes information flow in biological systems. It begins with DNA, a relatively long-lived information storage molecule, from which information typically flows in two directions: into new DNA molecules, during the process of replication, or into messenger RNA (mRNA), during the processing of transcription. mRNA is a relatively short-lived molecule that transfers information that is used to synthesize protein molecules by the ribosome. Proteins are often thought of as the building blocks of life. They serve a variety of purposes, ranging from molecular machines such as transmembrane ion transporters, to structural molecules like myosin, a major component of muscle fibers. There are some uncommon circumstances where information flows differently, for example RNA viruses encode their genomes in RNA, which can be reverse transcribed to DNA in a host cell. Proteins do seem to be a terminal output of this information flow: once a protein has been created, we are aware of no natural process that can work backwards to re-create the RNA or DNA that encoded it.

We’ll revisit these ideas at the end of this chapter, but first let’s establish some concepts that will help us to understand and even quantify information. These ideas have their roots in Boolean algebra and Information Theory. Bear with me while I introduce some concepts that may be new to you, and may initially seem unrelated.

Fig. 1 The central dogma of molecular biology represents information flow in biological systems. Blue pathways are generally observed in cellular life. Red pathways are observed in special cases such as RNA viruses. (Figure attribution: Narayanese at English Wikipedia, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.¶

Binary and decimal numerical systems¶

Humans most frequently use a base 10 or decimal numerical system for representing numbers. Base 10 means than there are ten available digits including zero. These are the digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. We represent numbers larger than 9 using multiple places: the ones place, the tens place, the hundreds place, and so on. These are the exponents of 10: the ones place is \(10^{0}\), the tens place is \(10^{1}\), the hundreds place is \(10^{2}\), and so on. When we write a decimal number with multiple places, such as 42, what we’re representing is a four in the tens place plus a two in the ones place, or \(4 \times 10^{1} + 2 \times 10^{0} = 42\).

You’ve probably heard that computers use a base 2 or binary numerical system to represent numbers. The base again describes the number of available digits, so in a base 2 or binary system, there are two digits, 0 and 1. These are defined as the binary digits. As in the decimal system, numbers larger than 1 are represented using multiple places. The places in a binary number are again based on exponents, but this time they are the exponents of 2. Instead of a ones place, a tens place, and a hundreds place, the first three places in a binary number are the ones place (\(2^0\)), the twos place (\(2^1\)), and the fours place (\(2^2\)). Thus the interpretation of the binary number 011 is \(0 \times 2^2 + 1 \times 2^1 + 1 \times 2^0 = 3\).

When working with numbers that may be other than base 10, by convention numbers would be written as \((n)_b\), where \(n\) is the number, and \(b\) is the base of the number. For example, \((11)_{10}\) represents the decimal number 11, because the base is 10. \((11)_2\) represents the decimal number 3: because the base is 2, we know that this is a binary number.

Here are some binary numbers and formulas for translating them to their decimal equivalents.

\((0)_2\) is the decimal number 0 (\(0 \times 2^0\))

\((1)_2\) is the decimal number 1 (\(1 \times 2^0\))

\((01)_2\) is also the decimal number 1 (\(0 \times 2^1 + 1 \times 2^0\))

\((11)_2\) is the decimal number 3 (\(1 \times 2^1 + 1 \times 2^0\))

\((110)_2\) is the decimal number 6 (\(1 \times 2^2 + 1 \times 2^1 + 0 \times 2^0\))

\((111)_2\) is the decimal number 7 (\(1 \times 2^2 + 1 \times 2^1 + 1 \times 2^0\))

A single binary digit (a zero or one) is referred to as a bit, and bits can be used to encode a lot more than just numbers.

Encoding messages in bits¶

Internally, computers send and receive messages that are encoded using electrical currents. To reduce errors in message transmission, the electrical currents are interpreted only as being off or on: there is less opportunity for error if there are only two states to choose from rather than three, four, five, or more. For example, think about guessing the answer to a question you’re unsure of on a multiple choice test. If there are only two choices, there are fewer opportunities to be wrong than if there are three or more choices. This is the reason that binary numbers are used to encode information in a computer. The digit zero can represent an electical current being off, and the digit one can represent an electircal current being on, such that the message 011 can be sent as off-on-on. The receiver of the message off-on-on could then know that the binary number 011 has been sent across the wire. But what does that message mean? The messages encoded by bits can be nearly anything, provided that the sender of the message and the recipient of the message have agreed on a coding scheme which describes how a message can be encoded in bits.

Transmitting a one-bit message¶

To illustrate a useful system that operates on the transmission of one bit of information, I’ll describe a photosensor for an outdoor spotlight. In this example, the photosensor is the sender of the message and the spotlight is the receiver of the message. The transmission of a zero from the photosensor to the spotlight could mean that it is currently light outside, and the transmission of a one could mean that it is currently dark outside. (The meanings of zero and one could be reversed: all that matters is that the sender and the receiver know what each value means.) The photosensor can monitor the available light, and send a message to the spotlight once per minute. If it is currently light outside, the photosensor will send a zero to the spotlight and the spotlight will turn off or remain off. If it is currently dark outside, the photosensor will send a one to the spotlight, and the spotlight will turn on or remain on. The photosensor is functioning as an on/off switch for the spotlight, transmitting one bit of information every minute.

There are couple of important things to consider in this example. First, the meaning of “currently light outside” and “currently dark outside” are embodied in the photosensor. It must make a decision on whether it is light or dark on it’s own, because it is only transmitting one bit of information (zero equals light and one equals dark). The message it sends isn’t complex enough to describe how light or dark it currently is outside - it’s effectively only flipping a switch on or off.

Transmitting more complex messages¶

To enable the transmission of more complex messages more bits can be used. One bit allows us to transmit two messages: 0 and 1, which in our photosensor example are interpreted as off and on, respectively. If our message is based on two bits we can transmit four messages, 00, 01, 10, or 11. A related example of this could be a light switch with four states: off, low brightness, medium brightness, and high brightness. If our message is based on three bits, we can transmit eight messages, 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, or 111. There is a pattern emerging here. If n is number of bits that you have available to send a message, the number of distinct messages that you can send is \(2^n\).

Decoding binary messages¶

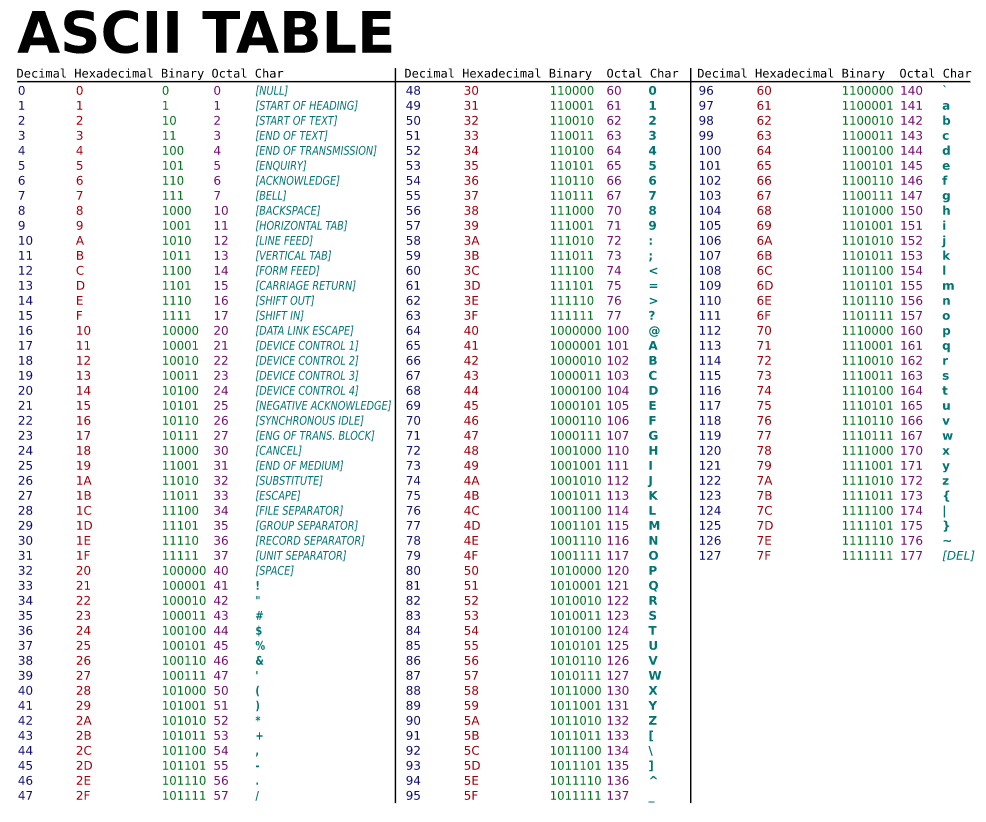

A historically relevant coding scheme is ASCII (Fig. 2). ASCII is a mapping from numbers to common English keyboard characters (as well as some common control characters that are mostly irrelevant for modern computers). This coding scheme defines how seven bit messages could be used to encode messages that (exclusively) use these characters. For example, this table tells me that in the ASCII coding scheme, the binary number 1000001 encode the capitol A character. Note that this particular table doesn’t include leading zeros in binary numbers, so for example, 0111111 encodes the character ?.

Fig. 2 The ASCII code chart. Notice that numbers are presented in a few different numical systems in this table: decimal (base 10), hexadecimal (base 16), binary (base 2), and octal (base8). All of the binary numbers in this table are based on seven bits, but leading zeros in binary numbers are unfortunately not presented in this table, making it a little less convenient to look numbers up. (Figure attribution: Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.)¶

If we have a message composed of seven-bit binary numbers, as we know that a message is encoded in ASCII, we can use this table to decode it. For example, the following sequence of symbols:

1001000 1100101 1101100 1101100 1101111 0100001

could be decoded to the message:

Hello!

Try to decode the message encoded in ASCII by these binary numbers:

1010001 1001001 1001001 1001101 1000101 0100000 0110010 0100000 1101001 1110011 0100000 1100011 1101111 1101111 1101100 0100001

Protein sequences are encoded in a base 4 system¶

The building blocks of DNA are four chemical compounds called adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine. We often represent these compounds with the abbreviations A, C, G and T, respectively. One of the primary roles of DNA in biological organisms is to encode the primary structure, or amino acid sequence, of proteins. As with computer systems, this information is represented based on discrete states, but in biological systems there are four states rather than two. Each position or place in an exon of a protein-coding DNA sequence can contain one of these compounds, and the linear order of the compounds can encode a message.

When first translated, proteins are composed of simpler units, the amino acids, and most organisms use 20 different amino acids to build proteins. Because there are four DNA bases (A, C, G, and T) and twenty amino acids, we need more than one base to transmit the message of what amino acid comes next in a protein from DNA to the ribosome. How many DNA bases we need depends on how many messages we want to be able to send, which in this case is 20 (for the twenty amino acids). So, how many DNA bases are needed to encode the 20 canonical amino acids?

We can determine the number of messages we can send in a base four system with a given number of places using the formula \(4^n\). So with one place (or one DNA base) we can send four messages. Since four is less than twenty, we’ll need longer messages to encode the twenty amino acids. If our message were composed of two bases, we could send \(4^2=16\) messages - that’s still less than twenty, so we’ll need more bases. If our message were composed of three bases, we could send \(4^3=64\) messages. This is more than twenty, which means that we can encode all of the amino acids (with some messages to spare) in three bases. It’s important to note that the number of places we can use must be a whole number - “2.5 bases of DNA” is not a meaningful quantity.

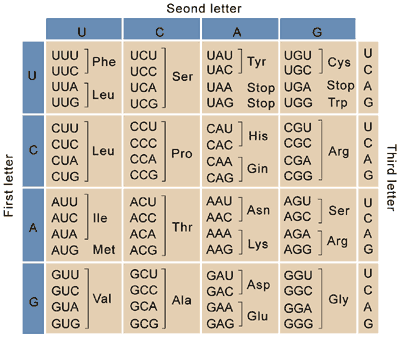

Amino acids are in fact encoded by three nucleotide bases, and the three base messages are referred to as codons. The mapping of codons to amino acids is referred to as the genetic code. Each codon represents exactly one amino acid, with the exception of some, the stop codons, which indicate the end of a message. Because there are 64 codons but only twenty-one messages that need to be transmitted (the twenty amino acids and the “stop” signal), some amino acids and the stop signal are represented by more than one codon. This is referred to as the redundancy of the genetic code.

Fig. 3 The vertebrate RNA genetic code. The corresponding DNA genetic code is identical, except that Us are replaced with Ts. (Figure attribution: NIH, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.¶

Decoding protein messages¶

We can use Fig. 3 to decode blueprints for proteins from DNA or RNA molecules. In addition to the stop codons mentioned above, to determine what protein sequence is represented by a DNA or RNA sequence we also need to pay attention to start codons. Unlike stop codons, there aren’t codons that exclusively indicate the start of a protein coding region. The AUG codon in RNA (or ATG in DNA) indicates the start of a protein coding region. It also encodes the amino acid methionine, and the start codon is translated so the resulting protein will start with a methionine (which may be removed post-translationally). If an AUG codon appears in the middle of a protein coding sequence, it doesn’t have any special meaning (it only encodes methionine in that case). Let’s look at a few examples.

Imagine we have the following RNA sequence.

AUGUAUGAGGGUACUAAUUAA

The first thing I would do if I were trying to decode this message by hand is identify the start codon, which in turn defines where the codons are. I then try to find some way to visually delineate the breaks between the codons. On paper, I might draw a line between each pair of codons. Here I’ll insert spaces.

AUG UAU GAG GGU ACU AAU UAA

Now I can look up each of these codons in the genetic code above, beginning with the start codon (which does get translated). If I look up AUG in Fig. 3, I see that that encode for the amino acid Met, or Methionine. The next codon, UAU, encodes for the amino acid Tyr, or Tyrosine. If I continue through this sequence until I hit a stop codon, I end up with the protein sequence:

Met - Tyr - Glu - Gly - Thr - Asn

The final codon, UAA, is a stop codon. Stop codons don’t get translated into anything - they just terminate the message.

In this example, our sequence started with the start codon and ended with a stop codon, but that’s not always going to be the case when you’re looking at an RNA sequence. Let’s work through another example to illustrate that.

CUUUUAUGCCUCGUCGUAGUGUGGAAUGAUGGCGUUC

Again, I’ll first identify where the start codon is and insert some spaces in the sequence to help me identify the codons.

CUUUU AUG CCU CGU CGU AGU GUG GAA UGA UGG CGU UC

Here we see that there are a few bases before the start codon. I didn’t bother to split those bases up from one another since they’re not relevant to this task because they preceed the start codon. Without referring to Fig. 3, I don’t yet know where the stop codon is in this sequence (or if there is one), so I started inserting spaces between my sequences beginning with the start codon, and I continued through the end of the sequence. Notice that I don’t have a full codon at the end of my sequence. Hopefully I’ll find a stop codon before I get to that point - if not, I have an incomplete and therefore probably useless message. Beginning again with my start codon, I decode the RNA sequence as follows:

Met - Pro - Arg - Arg - Ser - Val - Glu

Since UGA encodes a stop codon, this message ends before it reaches the end of the sequence. The bases following the stop codon are therefore not part of the protein message encoded by this DNA.

Translating protein sequences by hand doesn’t scale very well. If I need to do this for longer sequences (generally proteins will be much longer than six or seven amino acids long), it would be a slow and error prone process. When faced with a task like this, once we understand what we’re trying to do, it’s helpful to identify (or develop, if necesary) software that can help us. The scikit-bio Python library has functionality for translating DNA or RNA sequences into protein sequences. We can use scikit-bio in a Python 3 program or terminal as follows:

import skbio

# the following sequence is derived from NCBI reference sequence NM_005368.3

protein = skbio.RNA(

"AUGAAACCCCAGCUGUUGGGGCCAGGACACCCAGUGAGCCCAUACUUGCUCUUUUUGUCUUCUUCAGACUGCGCCAUGGG"

"GCUCAGCGACGGGGAAUGGCAGUUGGUGCUGAACGUCUGGGGGAAGGUGGAGGCUGACAUCCCAGGCCAUGGGCAGG"

"AAGUCCUCAUCAGGCUCUUUAAGGGUCACCCAGAGACUCUGGAGAAGUUUGACAAGUUCAAGCACCUGAAGUCAGAG"

"GACGAGAUGAAGGCGUCUGAGGACUUAAAGAAGCAUGGUGCCACCGUGCUCACCGCCCUGGGUGGCAUCCUUAAGAA"

"GAAGGGGCAUCAUGAGGCAGAGAUUAAGCCCCUGGCACAGUCGCAUGCCACCAAGCACAAGAUCCCCGUGAAGUACC"

"UGGAGUUCAUCUCGGAAUGCAUCAUCCAGGUUCUGCAGAGCAAGCAUCCCGGGGACUUUGGUGCUGAUGCCCAGGGG"

"GCCAUGAACAAGGCCCUGGAGCUGUUCCGGAAGGACAUGGCCUCCAACUACAAGGAGCUGGGCUUCCAGGGCUAGGC"

"CCCUGCCGCUCCCACCCCCACCCAUCUGGGCCCCGGGUUCAAGAGAGAGCGGGGUCUGAUCUCGUGUAGCCAUAUAG"

"AGUUUGCUUCUGAGUGUCUGCUUUGUUUAGUAGAGGUGGGCAGGAGGAGCUGAGGGGCUGGGGCUGGGGUGUUGAAG"

"UUGGCUUUGCAUGCCCAGCGAUGCGCCUCCCUGUGGGAUGUCAUCACCCUGGGAACCGGGAGUGGCCCUUGGCUCAC"

"UGUGUUCUGCAUGGUUUGGAUCUGAAUUAAUUGUCCUUUCUUCUAAAUCCCAACCGAACUUCUUCCAACCUCCAAAC"

"UGGCUGUAACCCCAAAUCCAAGCCAUUAACUACACCUGACAGUAGCAAUUGUCUGAUUAAUCACUGGCCCCUUGAAG"

"ACAGCAGAAUGUCCCUUUGCAAUGAGGAGGAGAUCUGGGCUGGGCGGGCCAGCUGGGGAAGCAUUUGACUAUCUGGA"

"ACUUGUGUGUGCCUCCUCAGGUAUGGCAGUGACUCACCUGGUUUUAAUAAAACAACCUGCAACAUCUCA"

).translate(stop='require')

protein

Protein

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Stats:

length: 179

has gaps: False

has degenerates: False

has definites: True

has stops: False

---------------------------------------------------------------------

0 MKPQLLGPGH PVSPYLLFLS SSDCAMGLSD GEWQLVLNVW GKVEADIPGH GQEVLIRLFK

60 GHPETLEKFD KFKHLKSEDE MKASEDLKKH GATVLTALGG ILKKKGHHEA EIKPLAQSHA

120 TKHKIPVKYL EFISECIIQV LQSKHPGDFG ADAQGAMNKA LELFRKDMAS NYKELGFQG

The above step translated an RNA sequence to a protein sequence for us, and then displayed the result to the screen. One difference to note is that we previously used three-letter codes to represent amino acids, but scikit-bio uses one-letter codes to represent amino acids. One-letter codes are more commonly used in practice, since they’re more concise.

Limitations of this analogy¶

Genomes contain messages other than protein sequences, so in reality the messages encoded by DNA in our genomes are more complex than a base 4 numerical system. For example, the structure that a chromosomal region adopts can impact whether genes in that region are expressed or not, which can have profound phenotypic impacts. Similarly, variations in splicing of mRNA messages result in different proteins from the same DNA sequence. There are higher-level messages that are encoded in our genomes. So, while in some ways we can relate the information contained in our genomes to the way information is stored in computers, our genomes are not just programs that are executed. Even the simplest cellular organisms are far more complex than the most complex machines of humankind! “An airplane is nothing if you compare it to a pelican,” observed Herman Dune.

Also ignored in this discussion is that additional characters are sometimes used to represent ambiguity in our knowledge of a DNA sequence, or to concisely represent more than one sequence. The IUPAC nucleic acid notation is what we’ve been using in this chapter, where A, C, G, and T represent adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine, respectively. Other characters are definited in this notation. For example, N is defined to mean either A, C, G, or T, and is thus commonly encountered in readouts of DNA sequences at positions where the base couldn’t be determined. These degenerate characters couldn’t be represented in the base 4 numerical system we’ve been discussing here. They also don’t exist in nature - we just use them to talk about DNA sequences.

Quantifying information¶

Information is a quantifiable concept, an idea that has its roots in Boolean algebra and in Claude Shannon’s work on Information Theory. As we discussed earlier, the most basic unit of information is the binary digit, or bit, which has two possible states. Depending on the domain, the symbols representing these two states might be 0 and 1, yes and no, + and -, true and false, or on and off. When you answer a “yes/no” question in a conversation, or a “true/false” question on an exam, you’re providing one bit of information.

Information is technically defined as a sequence of symbols that can be interpreted as a message. To put these terms in the context of our binary number examples above, our message is a decimal number, our symbols are 0 and 1, and the sequence is the ordered collection of symbols, such as 011. The number of places (let’s call that \(p\)), and the number of symbols (let’s call that \(n_{symbols}\)) define the number of different messages (\(n_{messages}\)) that can be encoded as: \(n_{messages} = n_{symbols}^p\).

Let’s apply this formula to determine how many messages can be sent with one byte of information:

n_symbols = 2 # we'll use the two available binary digits, 0 and 1

p = 8 # because there are 8 places, or bits, in a byte

print(n_symbols**p)

256

Since bases in a DNA sequence are represented with four characters, each position in a sequence contains two bits of information. We know this because we could represent all four bases using two places in a binary number. For example, 00 could represent A, 01 could represent C, 01 could represent G, and 11 could represent T. These assignments of binary numbers to DNA bases is arbitrary.) In other words, if we have two symbols and two places, we can send four messages (\(2^2=4\)), so one base of DNA represents 2 bits of information. A DNA sequence that is 100 bases long would therefore contain 200 bits of information.

More generally, if we send a message using a numerical system with \(s\) symbols, and our message is \(p\) places long, the number of bits that are sent would be \(n\) in the following equation: \(s^p = 2^n\). We could solve for \(n\) as: \(n = \log_{2}s^p\).

The genetic code¶

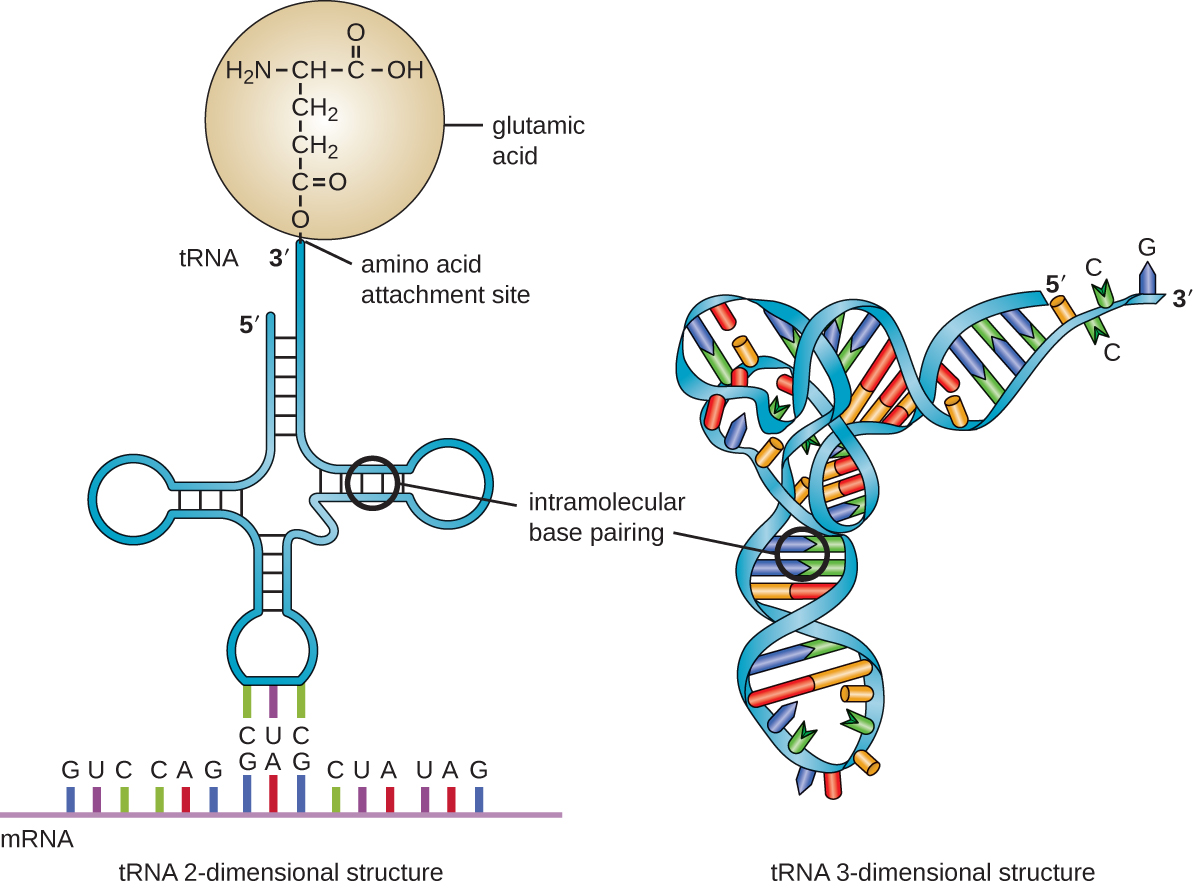

As mentioned above, the genetic code describes the mapping of codons to amino acids. This mapping is embodied in an organism’s transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules. As illustrated in Fig. 4, one end of the folded tRNA contains the “anticodon loop”, which is the complementary sequence to the mRNA’s codon. On the other end of the tRNA is the acceptor stem, which contains the amino acid attachment site. Through interaction with an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase, the amino acid corresponding to the anticodon is covalently linked to the acceptor stem. During translation, a tRNA’s anticodon pairs with a codon in a messenger RNA (mRNA) inside the ribosome and thereby provides the next amino acid needed for protein synthesis.

Fig. 4 The secondary and tertiary structure of a transfer RNA (tRNA) molecule. (Figure attribution: This image was obtained from OpenStax Microbiology, a free microbiology text book, and is licensed under CC-BY. OpenStax Microbiology can be accessed for free at https://openstax.org/books/microbiology/pages/1-introduction.)¶

Fig. 4 also illustrates two different views of the structure of a tRNA molecule. The secondary (\(2^o\)) structure is presented on the left, and the tertiary (\(3^o\)) structure is presented on the right. For a nucleic acid molecule, like tRNA, the secondary structure refers to the base pairing interactions in a folded molecule. The tertiary structure refers to the three-dimensional structure that the molecule takes inside of an organism. The primary (\(1^o\)) structure, which isn’t illustrated here, refers to the linear sequence of nucleotides in the tRNA molecule. The primary structure of a phenylalanine tRNA (i.e., tRNAPhe) from yeast in FASTA format, for example, is as follows.

>4TNA:A|PDBID|CHAIN|SEQUENCE

GCGGAUUUAGCUCAGUUGGGAGAGCGCCAGACUGAAGAUCUGGAGGUCCUGUGUUCGAUCCACAGAAUUCGCACCA

Each level of structure contains some information about the other levels. For example, if we were to examine the primary structure of tRNAPhe, we might find that there are stretches of certain bases that could form stable base pairing interactions with each other. That could help us to make a prediction about the secondary structure of tRNAPhe. We could use that information, along with knowledge about the physics of nucleic acid molecules to make predictions about how the molecule would fold inside of a cell (i.e., its tertiary structure). If we knew the tertiary structure of a molecule with similar primary structure to tRNAPhe, that information would also be very helpful in predicting the tertiary structure of tRNAPhe because we expect nucleic acids or proteins with similar primary structures to also have similar secondary and tertiary structures, though this isn’t always the case.

The primary and secondary structure of a molecule alone doesn’t currently allow us to make perfect predictions about the tertiary structure that a molecular will adopt. Personally, I think additional information is needed so this type of prediction won’t ever be entirely reliable, but predicting a molecule’s tertiary structure from its primary structure is a classic problem in bioinformatics.

Summary¶

In this section we explored different numerical systems, including binary and decimal numerical systems. We additionally discussed relationships between how computers and organisms represent information, introduced the genetic code, and used the genetic code to decode protein messages from RNA sequences.